n a small village on the fringes of a rainforest, not far from the border between Malaysia and Thailand, there is a man who was once a pangolin trader. In fact, if the stories he tells us are true, he could well be one of the most prolific pangolin traders the country has ever seen.

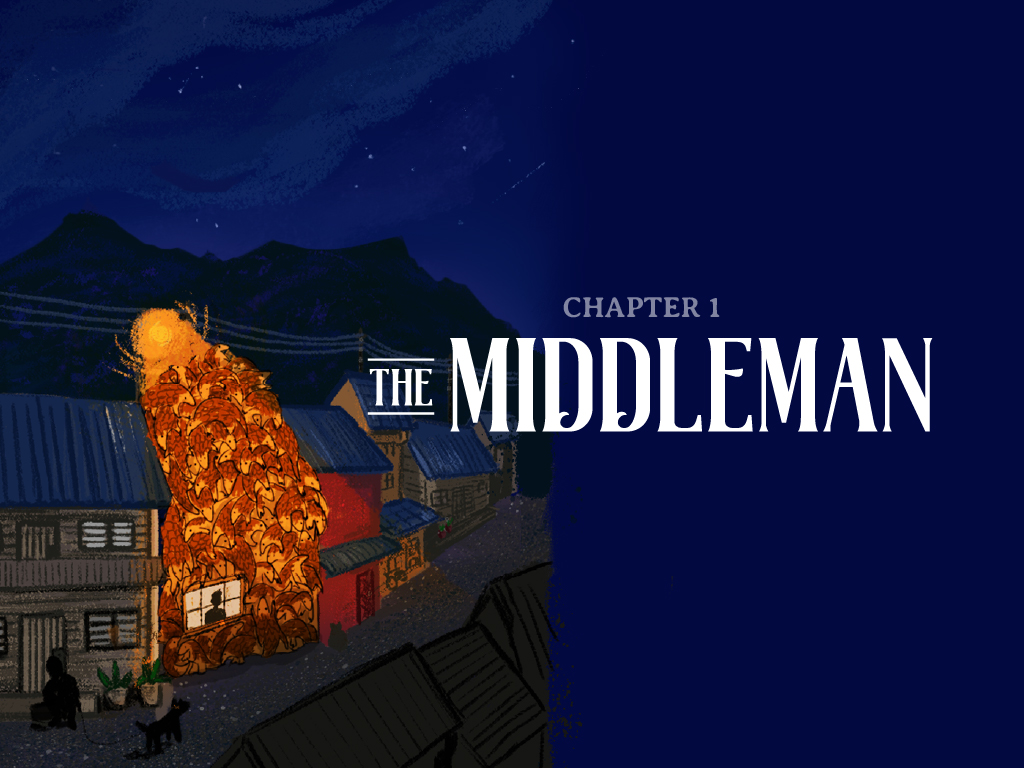

We meet him late in the evening, in his rather quaint village home – a home with orange walls and lavender windows, clustered close with many other similarly colourful homes along the narrow alleys of his village.

On the corner of one of these alleys is a restaurant specialising in forest game, a testament to life near the jungle, where meat, is meat, is meat.

The trader’s living room is a bizarre setting for a discussion on organised crime. On the wood plank walls hang old family photos and faded wedding portraits. His pet dogs are lazing by the door. The ceiling fan beats away the warm night air.

“In the past, I was moving a lot of stock, hundreds of baskets,” he boasted. “I’m not lying to you, at least three tonnes a month, delivered right to my doorstep.” - Pangolin trader

Across the small living room, his two young children are fiddling with their phones. His son interrupts our conversation at one point to ask if he can have durian for dessert.

“Careful of the thorns,” he shouts after the boy, then politely offers us some. We decline.

Also on offer – five casques of the critically endangered helmeted hornbill, which he has laid out on a chair before us. These casques, known as “red ivory”, are the solid structure above the hornbill’s beak that the males use for head-to-head combat. They are also the latest fad in wildlife smuggling, with a pound-for-pound street price up to five times higher than elephant ivory.

But he has left the wildlife trade, he insists. The casques are just leftover goods from a former life. He retired after being caught in possession of pangolins in 2014.

“In the past, I was moving a lot of stock, hundreds of baskets,” he boasted. “I’m not lying to you, at least three tonnes a month, delivered right to my doorstep.”Three tonnes of pangolins would equal around 600 individual pangolins, or 20 pangolins every day – a staggering amount, considering pangolins are critically endangered in Malaysia.

“I don’t catch pangolins, the Asli (indigenous people) catch them for me,” he says, his bulky frame shifting in the plastic beach chair he uses indoors. “How can we do it? It’s too tough!” He once tried to go hunting with them and was left winded.

Based on his descriptions, the trader is a middleman. Someone who sources pangolins from poachers and hunters, then sells them on to the syndicates – a key link in the pangolin smuggling trade.

“From Malaysia, they (the syndicates) send them by car to Bukit Kayu Hitam (a border checkpoint),” he explains. “Mostly they pass through there. Or they pass at Golok. They can also pass through Kaki Bukit.” He name drops one particular smuggler who uses the Golok route, saying he once handed him elephant ivory to smuggle across.

“The Malaysian buyers cover the smuggling from Malaysia all the way to Laos. That is what I know. There is a boss in Malaysia, and a boss in Laos. Everything is transported by car.”His selling price varies by buyer, by season, and that price is passed on to the poachers: “The highest price I ever sold at was RM400 (US$96) per kg at one point. So at the time I was buying for RM370. I hear it can fetch up to RM1,000 (US$240) in Laos.”

But the trade is changing, according to his observations.

It’s all coming from Indonesia now, by boat, but we don’t know where they land and where they load up. There is less stock in Malaysia now, so they rely on Indonesian stock.He now spends his days managing some of the durian and rubber plantations that nibble away at the edges of the forest, producing commodities that travel the world to where the demand is. He supervises the labour, takes a percentage of sales.

“It was hard work trading pangolins,” he recounts. “I earned about RM20 to RM30 per kg, not much.” His was a wholesale business subsisting on volume, not high premiums.

“Sometimes (when the price was too low), it was cheaper to just throw them away.”

Over the course of many months, R.AGE journalists spoke to people from the pangolin trade like him, often undercover or on condition of anonymity. These conversations paint a picture of an underground trade stretching back decades, operating like an open market, where poachers, buyers and smugglers jostle for market share, and prices are decided by market forces.

The demand that fuels the trade – China’s insatiable appetite for this little-known scaly anteater. Reports from government enforcement agencies and international NGOs all agree that the overwhelming majority of smuggled pangolins are destined for China, where its scales are used in traditional Chinese medicine to cure a variety of ailments from inflammation to poor lactation for new mothers, and its meat is served as a status-symbol delicacy.

But to get the pangolins to China, there are borders to cross.

In a small village on the fringes of a rainforest, not far from the border between Malaysia and Thailand, there is a man who was once a pangolin trader. In fact, if the stories he tells us are true, he could well be one of the most prolific pangolin traders the country has ever seen.

We meet him late in the evening, in his rather quaint village home – a home with orange walls and lavender windows, clustered close with many other similarly colourful homes along the narrow alleys of his village.

On the corner of one of these alleys is a restaurant specialising in forest game, a testament to life near the jungle, where meat, is meat, is meat.

The trader’s living room is a bizarre setting for a discussion on organised crime. On the wood plank walls hang old family photos and faded wedding portraits. His pet dogs are lazing by the door. The ceiling fan beats away the warm night air.

Across the small living room, his two young children are fiddling with their phones. His son interrupts our conversation at one point to ask if he can have durian for dessert.

“Careful of the thorns,” he shouts after the boy, then politely offers us some. We decline.

Also on offer – five casques of the critically endangered helmeted hornbill, which he has laid out on a chair before us. These casques, known as “red ivory”, are the solid structure above the hornbill’s beak that the males use for head-to-head combat. They are also the latest fad in wildlife smuggling, with a pound-for-pound street price up to five times higher than elephant ivory.

But he has left the wildlife trade, he insists. The casques are just leftover goods from a former life. He retired after being caught in possession of pangolins in 2014.

“In the past, I was moving a lot of stock, hundreds of baskets,” he boasted. “I’m not lying to you, at least three tonnes a month, delivered right to my doorstep.”Three tonnes of pangolins would equal around 600 individual pangolins, or 20 pangolins every day – a staggering amount, considering pangolins are critically endangered in Malaysia.

“I don’t catch pangolins, the Asli (indigenous people) catch them for me,” he says, his bulky frame shifting in the plastic beach chair he uses indoors. “How can we do it? It’s too tough!” He once tried to go hunting with them and was left winded.

Based on his descriptions, the trader is a middleman. Someone who sources pangolins from poachers and hunters, then sells them on to the syndicates – a key link in the pangolin smuggling trade.

“From Malaysia, they (the syndicates) send them by car to Bukit Kayu Hitam (a border checkpoint),” he explains. “Mostly they pass through there. Or they pass at Golok. They can also pass through Kaki Bukit.” He name drops one particular smuggler who uses the Golok route, saying he once handed him elephant ivory to smuggle across.

“The Malaysian buyers cover the smuggling from Malaysia all the way to Laos. That is what I know. There is a boss in Malaysia, and a boss in Laos. Everything is transported by car.”His selling price varies by buyer, by season, and that price is passed on to the poachers: “The highest price I ever sold at was RM400 (US$96) per kg at one point. So at the time I was buying for RM370. I hear it can fetch up to RM1,000 (US$240) in Laos.”

But the trade is changing, according to his observations.

It’s all coming from Indonesia now, by boat, but we don’t know where they land and where they load up. There is less stock in Malaysia now, so they rely on Indonesian stock.He now spends his days managing some of the durian and rubber plantations that nibble away at the edges of the forest, producing commodities that travel the world to where the demand is. He supervises the labour, takes a percentage of sales.

“It was hard work trading pangolins,” he recounts. “I earned about RM20 to RM30 per kg, not much.” His was a wholesale business subsisting on volume, not high premiums.

“Sometimes (when the price was too low), it was cheaper to just throw them away.”

Over the course of many months, R.AGE journalists spoke to people from the pangolin trade like him, often undercover or on condition of anonymity. These conversations paint a picture of an underground trade stretching back decades, operating like an open market, where poachers, buyers and smugglers jostle for market share, and prices are decided by market forces.

The demand that fuels the trade – China’s insatiable appetite for this little-known scaly anteater. Reports from government enforcement agencies and international NGOs all agree that the overwhelming majority of smuggled pangolins are destined for China, where its scales are used in traditional Chinese medicine to cure a variety of ailments from inflammation to poor lactation for new mothers, and its meat is served as a status-symbol delicacy.

But to get the pangolins to China, there are borders to cross.