WITH no small amount of glee, I happily informed students who were late handing in their assignments that Wikipedia was going to be “blacked out” for a day.

That was last Wednesday, the day where Internet giants like Wikipedia, Google, Facebook and Reddit decided to “black out” their sites in protest against the “Stop Online Piracy Act” (SOPA) bring tabled in the US.

Depending on the site, the “black out” meant different things. For Wikipedia, users browsing the English language website last Wednesday would find a message popping up instead, telling them to “imagine a world without free knowledge.”

Indeed, if you were a student looking for help on Wikipedia that very instant, you couldn’t do anything but experience what living without Wikipedia would be like.

Other sites, like Reddit, chose to “censor” every single line of content. You could see that content had been written and shared, but you couldn’t read what it was – no thanks to a thick black line running through the text.

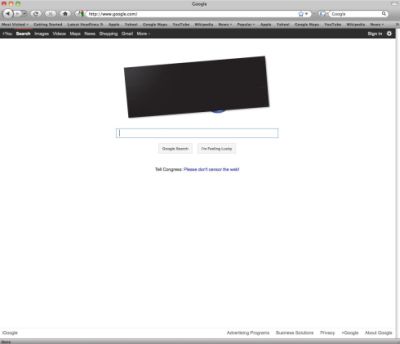

Google adopted a safer approach, choosing to show US users only a blacked out Google Logo on its front page. I can only imagine the pandemonium that would ensue if Google were to go down.

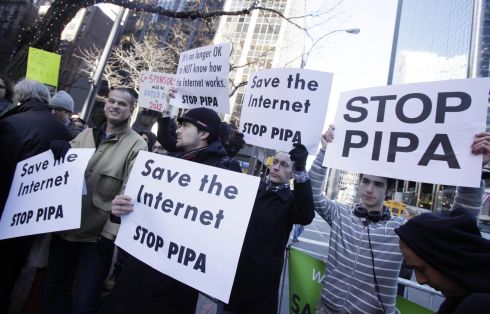

So obviously, there was a big hoo-hah over the Internet about this piece of legislation called SOPA, and to a lesser extent, its cousin called the “Protect IP Act” (PIPA). And it grabbed the attention of the Internet audience. But, what exactly is this act about? And why should you and I care about it?

Let me do my best to break it down to you. SOPA is piece of US legislation that seeks to allow companies that think their stuff is being pirated to file a lawsuit against websites outside of the United States and force action that would stop those websites from being accessed by people in the US.

Confused? Here’s how it works: Say you’re a big Hollywood company and you’ve released your brand new blockbuster movie. But as you are sending the video files to the cinemas, you discover it’s already on some website called “ShareYourBigFiles.ru”.

Now, you think, “Oh no, if people are downloading the movie, I can’t get them to buy movie tickets from the cinema.” So you try to file a lawsuit.

Unfortunately, the website’s owners are based outside the US and the actual servers are also located in another country. This means you’ll need to go through the laws of their country – laws which may not take US copyright law quite as stringently – to bring them to court.

What can a company in these dire straits do? The supposed answer is SOPA, which would allow the company to file a lawsuit in US courts, and block the offending website from being accessed inside the US. They are not shutting down the website, but removing it from the screens of US citizens.

“Wait a minute,” you think, “that sounds reasonable.” Well, if you’ve been listening to the big media company’s side of the story, you might feel that way too. But here’s why technology companies such as Google and Facebook and Wikipedia have been rallying supporters to object to SOPA.

Buried deep in SOPA’s legislation, is this phrase: “A service provider shall take technically feasible and reasonable measures designed to prevent access by its subscribers located within the United States to the foreign infringing site (or portion thereof) that is subject to the order…Such actions shall be taken as expeditiously as possible, but in any case within five days after being served with a copy of the order, or within such time as the court may order.”

What this means is that through SOPA, a media company can essentially tell an Internet Service Provider to censor a website by going to court and obtaining a court order. And by pursuing a case as stringently as possible, it can essentially erase a website from the face of the American Internet. Now, if the US sets this precedent, which nations do you think will soon follow suit?

The part that’s dangerous about this is that it starts to make the Internet Service Provider responsible for policing content. In Malaysia, we’re fortunate to have the Bill of Guarantee under the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) to ensure the Internet shall remain uncensored. It’s a benefit we should really be thankful for.

Imagine if TMNet now is responsible for blocking sites like YouTube simply because someone posted “pirated” content? Or if DropBox needed to cease its service because some pirated files were found on someone’s account? The thought is ludicrous, but it’s something that Sopa’s shown us we’re taking for granted.

The Internet as we experience it today is free and fluid. You can go online and start a blog and post your own opinions. You can use Facebook to easily connect with friends, and share media. Even the much-maligned Bit-Torrent technology is used to deliver useful information faster (it’s not all about piracy). On the Malaysian front, Information, Communications and Culture Minister Datuk Seri Rais Yatim has said last year that the country is committed to keeping the Internet free.

The proponents for a free Internet are against SOPA not because it’s not reasonable to want to protect your ideas and original work, but because of its deeper ramifications, chiefly taking us down that slippery slope of Internet censorship. Some 4.5 million people signed a pledge last Wednesday to oppose Sopa and any form of legislation that could lead to Internet censorship. Wikipedia’s message calls SOPA a “legislation that could fatally damage the free and open internet.”

For the rest of us, we really need to ask ourselves: “So, how much would you like your Internet to remain free and open?”

Appreciate the freedom you have today. Oh, and appreciate Wikipedia too. Let’s hope the Internet never black out again.

* David Lian has tried using the Internet in China where censorship is heavy (you can’t even get to Facebook) and it’s really not fun. Tweet him at @davidlian.

Tell us what you think!